Glue-sniffing, theft and violence marked Andrew Ong’s teenage years.

While his peers were preparing for their ‘O’ Level exams, he was getting ready for a gang fight.

When he was 17, he was arrested for rioting, and was sentenced to 30 months in jail and five strokes of the cane.

“My family was going through a rough patch and the gang became my family,” Andrew, now 41, says. “I found a sense of belonging, mutual understanding and support. We were there for each other, although we were misguided.”

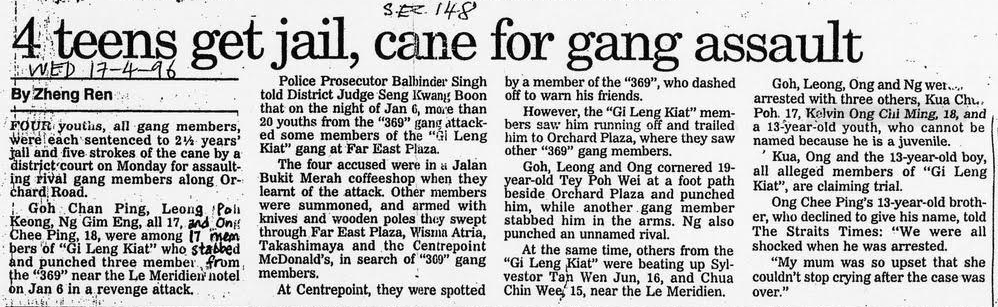

“I keep this and also the letters I wrote when I was in prison to remind me of my past,” says Andrew, who used to go by the name Kelvin Ong. The newspaper clipping from his youth was given to him by his lawyer.

It was only during his term at the now-closed Queenstown Remand Prison that Andrew found the understanding and support he craved. It came from an unexpected source: A Bible somebody had left in his cell.

Andrew had gone to church before, and had people share Christ with him. “So I knew about Him, but I didn’t know Him,” he says.

“As a young boy I was like, ‘Wow this guy zai (cool) man, this Jesus is a solid guy!’”

When he encountered Jesus through the Bible, Andrew says he was intrigued by “His love, how He spoke out for the down and out, for the marginalised, how wise and witty He was with his answers and rebuttals to the Pharisees”.

“As a young boy I was like, ‘Wow this guy zai (cool) man, this Jesus is a solid guy’,” he recounts with a laugh.

“As I read more of His teachings, I saw how much love He has, and how holy He is at the same time. That part is really important – I was convicted of my sin, and I repented,” he says.

Double or nothing

Andrew was thinking of appealing for a reduction in his jail sentence. Initially, his cellmates and even the prison officer tried to dissuade him.

“At that time the High Court judge was notorious for being very stern; appeals that went through him were often tambah (added to).”

The judge would double the sentence of whoever appealed and was found wasting his time or unrepentent, Andrew said.

“My sentence was 30 months and five strokes of the cane. If I had lost my appeal, it might have become 60 months and 10 strokes of the cane. That was his reputation – 90% of his cases would go into tambah.

“That’s why the fear factor was so strong. The odds were against me. I was fearful. As a 17-year-old boy, I was not strong emotionally. So I prayed and God gave that word to go ahead.

“I really went by faith and obedience … I remember that day in court – seeing the High Court Judge face to face, watching my lawyer do the talking, and observing how God orchestrated everything. I felt like I was in the eye of the storm.”

“I was fearful – as a 17-year-old boy I was not strong emotionally. So I prayed and God gave the word to go ahead with the appeal.”

In the end, the judge acceded to the appeal.

“We won and the judge even complimented my lawyer for doing a great job,” recalls Andrew.

His sentence was drastically reduced. He had already been in prison for four months and just needed to serve out another two more months.

“I learnt that after he reviewed the case, all my accomplices who were already serving their sentences had their sentences also drastically reduced, even though they didn’t appeal,” recalls Andrew.

“So it felt like I was blessed to be a blessing when I stepped out in faith. A blessing is not only for you but for others as well.

“The whole process was so surreal, like ‘what just happened?’ It had to be God,” says Andrew in wonder.

“You cannot do anything at all in prison – use your network or whatever – to make your circumstances more favourable. You really are at the mercy of God’s hand. You can only pray and depend on Him to orchestrate things around you.”

Kelvin Ong is no more

Andrew eventually returned to school as a private student, graduated with a bachelor’s degree in communications management, and launched a career in marketing and communications.

Following a four-year work stint in Vietnam, he now heads corporate partnerships at a social enterprise.

So transformed is his life that he has even changed his name.

One day as he was reading about Jesus inviting Peter and Andrew to follow Him (Matthew 4:18-19), he felt his spirit stir. “I felt as if Jesus was calling out to me as ‘Andrew’,” he says.

“The old me (Kelvin Ong) is no more. Now I am Andrew, with a new mission in life …

“I embrace God’s call. I’m no longer looking back.”

Andrew also built a desire to use his story to help others re-write theirs.

It led him to join Architects of Life (AOL), a social enterprise focusing on reaching ex-offenders and at-risk youth, among others. It conducts rehabilitation, reintegration and support programmes for youths residing in instituted hostels, prison inmates and their families.

“When I came out, I spent a lot of time searching for role models. I was always thinking to myself that if I had a mentor to help me I could have at least navigated or had some clarity for the decisions I made.

“At that point (in the late 1990s), there were only a handful of ex-offenders that came out to share their stories,” he says.

A life repurposed

For Andrew, ex-offenders don’t need sympathy, “they need empathy”.

As an AOL mentor, Andrew and his peers mentor youth-at-risk at various institutions, sharing with them their own stories, “not to glamourise what we did, but so they know that we know what we are talking about”.

“The old me (Kelvin Ong) is no more. Now I am Andrew, with a new mission in life … “

“Those that come out also have a lot of insecurities, a lot of fears, questions about practical issues,” Andrew says. “If we come from the same background we can connect straightaway. We build that rapport, gain their respect and then we can advise and speak into their lives. I think that’s very important.”

AOL does not just aim to re-integrate ex-offenders and youth-at-risk into society. But to mentor and encourage them to become “archetypes” of society.

An archetype is “role model or champion, a pattern that you should follow”, Andrew says.

“We’re not interested in you just re-integrating, lying low and being ashamed of your past, hiding your past. Come out, tell your story, make good your past for the betterment of society.”

Andrew’s story of his transformed life, along with five other ex-offenders, is featured in the book From Stereotypes to Archetypes.

Andrew and his wife, Sharmaine, on a holiday in Australia, at the 12 Apostles in Victoria.

“This book helps us understand their plight and hope to better appreciate the need to give them a second chance,” Teo Ser Luck, former Minister of State for Trade and Industry/Mayor, North East District, writes in the book.

Andrew believes much more can be done, especially for those at risk of re-offending.

“Don’t label ex-offenders, don’t limit their potential because of their past. The past does not define who they can be.

“To be honest, there are more failures than success stories,” he said.

In the last few years, AOL has been managing to gather more ex-offenders together to help them fulfil their purpose.

“We hope to be a community,” he said. “There are a lot of stories out there, but everyone’s doing their own thing. If we can bring all together through a collaboration, that would have a greater impact.”

Architects of Life’s vision is for every youth-at-risk and ex-offender to defy stereotypes to become archetypes that positively impact the world.

Ultimately, Andrew says his conviction comes from the power of the Gospel to “redeem and repurpose”.

“If anyone is in Christ, he is a new creation. The old has gone and the new is here,” he says, citing 2 Corinthians 5:17.

“I hope there’ll be more acceptance … don’t label them, don’t limit their potential because of their past. The past does not define who they can be.

“Who did God choose as His disciples?” he asks. “Fishermen, tax collectors, the sinners.

“He didn’t choose those who were doing well. So in the same light I think we can show society that these individuals can surprise you with what they can do.”

This is an excerpt of an article that first appeared in Salt&Light.

Click here to join our Telegram family for more stories like Andrew’s.

I was marked absent for all my O’Level subjects … I was that deeply involved in drugs

Addicted to drugs for 40 years, he felt no hope of change … until an encounter in a garden